Introduction

Fast fashion has transformed the global clothing industry, making trendy apparel affordable and accessible. Every stage of a garment’s life cycle, from fiber production to post-consumer waste, releases pollutants into our rivers and oceans. This pollution isn’t just cosmetic; it’s toxic, persistent, and often invisible to the naked eye.

The fashion industry is one of the largest consumers and polluters of freshwater globally.

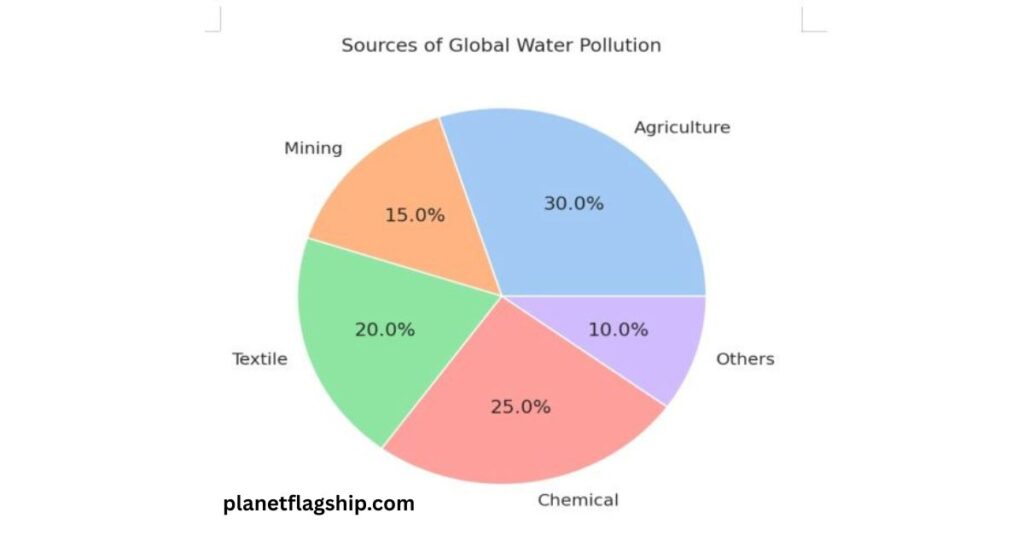

Textile dyeing alone is responsible for around 20% of global industrial water pollution. Worse still, synthetic fibers like polyester shed microplastics with every wash, adding to the growing microplastic load in aquatic ecosystems. These pollutants harm aquatic life, disrupt ecosystems, and ultimately threaten human health through the food chain.

1. The Water-Intensive Nature of Fashion Production

The fashion industry is among the most water-intensive industries in the world. Water is used at nearly every stage of garment production:

Cotton’s Thirst

Take cotton, for example. It’s one of the most common materials in clothing, but it’s also one of the thirstiest. Making a single cotton T-shirt can use over 2,700 liters of water—that’s enough drinking water for one person for nearly three years (WWF, 2013). Most of this water is used during farming, especially in hot, dry countries like India and Pakistan, where water is already in short supply.

Dyeing Disaster

After the cotton is harvested, the next water-hungry process begins: dyeing and finishing. Textile dyeing is the second-largest source of water pollution worldwide (UNEP, 2019). Toxic dyes, salts, and heavy metals are used to color fabrics—and in many countries, these chemicals are dumped straight into rivers without treatment.

2. Chemical Waste: Turning Rivers Toxic

In places where many of our clothes are made, like Bangladesh or Indonesia, you’ll find rivers that have literally turned dark purple, blue, or black from textile waste.

READ MORE: Climate Refugees Explained: The Hidden Human Cost of Climate Change

What’s in the Water?

Factories often release untreated wastewater containing:

Chromium

Lead

Mercury

Formaldehyde

These are not just harmful to fish, they’re hazardous to people too. Communities living near these rivers often suffer from skin diseases, stomach issues, and in some cases, even cancer.

Water Usage and Pollution by Textile Process

| Stage | Water Usage (Liters/kg) | Key Pollutants |

| Cotton Cultivation | 10,000 | Pesticides, fertilizers |

| Fabric Dyeing | 150 | Heavy metals, azo dyes |

| Garment Washing | 20 | Detergents, microplastics |

| Consumer Laundry | 40 | Microfibers, detergents |

When Rivers Die

These chemicals don’t just pollute, they kill. Fish populations drop, aquatic plants die off, and oxygen levels plummet. In places like the Buriganga River in Bangladesh, once home to thriving fish populations, there’s barely any life left.

3. The Microplastic Nightmare

Even when clothes look “clean,” they may still be polluting the planet—quietly, invisibly.

What Are Microfibers?

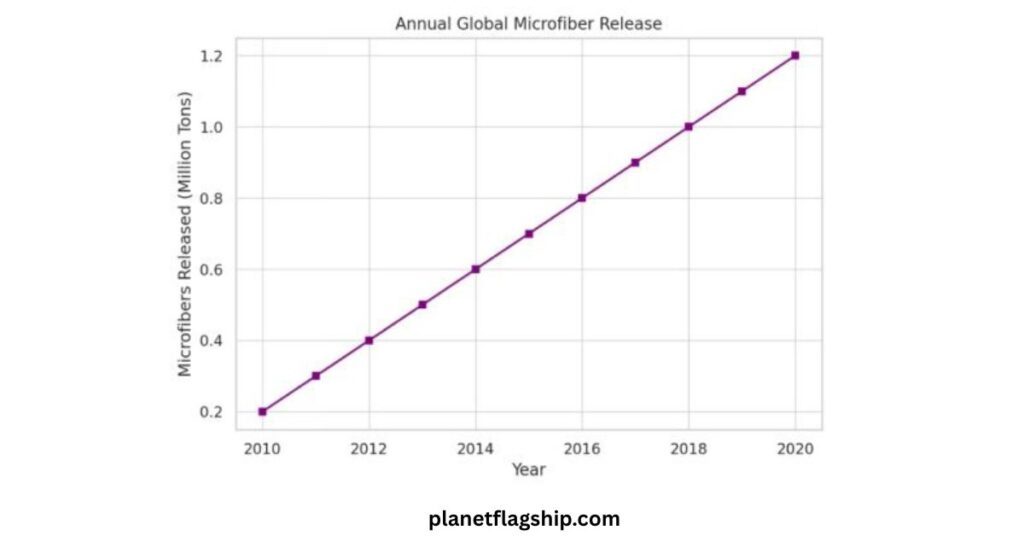

Every time you wash synthetic fabrics like polyester or nylon, they release tiny fibers called microplastics. These particles are too small for water treatment plants to catch, so they end up in rivers and eventually the oceans. According to one study, a single wash of synthetic clothing can release over 700,000 microfibers.

Why Does This Matter?

Once in the ocean, microplastics are eaten by fish, plankton, and even whales. These particles:

Disrupt digestion and reproduction in marine animals.

Carry toxic chemicals that accumulate in the food chain.

Eventually ends up on our plates via seafood.

4. Clothes That Don’t Just Disappear

Let’s not forget what happens to our clothes when we’re done with them. Thanks to fast fashion’s “wear it once” culture, most garments are thrown away after just a few uses.

Mountains of Waste

It’s estimated that 85% of all textiles end up in landfills or are burned (EPA, 2017). But in some places, the waste doesn’t even make it that far; it’s dumped illegally into rivers or along coastlines.

The Second-Hand Problem

Some of our donated clothes are shipped to developing countries like Ghana and Kenya. These countries often receive more clothing than they can use, and the excess is dumped, often near rivers or in open landfills, where it eventually finds its way into water bodies.

5. Pollution Hotspots: Real-Life Examples

The environmental cost of fast fashion isn’t theoretical; it’s very real in many parts of the world.

Citarum River, Indonesia

Once a source of drinking water and fish, this river is now one of the most polluted in the world. More than 500 textile factories discharge waste into it. People nearby still use the water to bathe and wash clothes, despite the risks.

Dhaka, Bangladesh

The capital of Bangladesh is home to thousands of garment factories. Rivers like the Buriganga are heavily polluted with textile waste. The water is black and toxic, and the river no longer supports aquatic life.

Nairobi River, Kenya

Here, rivers are polluted not only by local waste but also by the global second-hand clothing trade. When donated clothes can’t be resold, they’re dumped in or near waterways.

6. Who’s Responsible?

Factories in Poor Countries?

Not entirely. These factories often operate in countries with weak environmental laws because big brands seek cheap labor and minimal regulation.

The Brands?

Yes, but many hide behind “green” marketing while continuing to produce millions of garments every year. Some have “eco-friendly” collections that make up less than 1% of their overall output.

Us, the Consumers?

Our desire for cheap, trendy clothes drives demand for fast fashion. We often overlook where our clothes come from and what happens after we toss them.

7. What Can Be Done?

There are real, actionable steps we can take to reduce fast fashion’s impact on water.

Cleaner Production

Some companies are switching to waterless dyeing methods or using closed-loop systems that recycle wastewater. Techniques like digital printing and natural dyes also reduce pollution.

Better Waste Management

Governments in manufacturing countries need to enforce strict wastewater treatment regulations. Brands can help by investing in cleaner technologies and ensuring their suppliers follow environmental guidelines.

Conscious Consumer Choices

Buy less, buy better. Invest in clothes that last longer.

Choose natural fibers over synthetics.

Wash clothes less often, and use microfiber filters.

Genuinely sustainable support brands (not just greenwashing).

Policy and Regulation

Governments should implement Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) laws that make brands responsible for what happens to clothes after they’re sold. And globally, we need stronger environmental treaties to regulate textile pollution—just like we do with carbon emissions or plastics.

ALSO READ: How does greenwashing mislead consumers about sustainability?

How does fast fashion pollute rivers and oceans?

Fast fashion pollutes water through excessive water use, toxic textile dyes, untreated industrial wastewater, and microplastics released from synthetic fabrics during washing. These pollutants flow into rivers and eventually reach oceans.

Why is textile dyeing considered so harmful to water bodies?

Textile dyeing uses heavy metals, azo dyes, and toxic chemicals. In many countries, this wastewater is discharged untreated into rivers, making water toxic for aquatic life and unsafe for nearby communities.

What are microplastics, and how do clothes create them?

Microplastics are tiny plastic fibers released when synthetic clothes like polyester are washed. These fibers bypass water treatment systems, enter oceans, and accumulate in marine organisms and the human food chain.

Are consumers responsible for fast fashion pollution?

Yes, consumer demand for cheap, trendy clothing drives fast fashion production. Overbuying, frequent washing, and quick disposal of clothes increase water pollution and textile waste.

How can fast fashion’s impact on water pollution be reduced?

The impact can be reduced by buying fewer, higher-quality clothes, choosing natural fibers, washing less often, supporting truly sustainable brands, and enforcing strict environmental regulations on textile production.

Conclusion

The story of fast fashion isn’t just about cheap clothes; it’s also about polluted rivers, dead fish, toxic water, and microplastics in our oceans. The environmental costs are hidden behind the seams of our everyday outfits, but they are very real and growing.

Whether it’s choosing more sustainable brands, washing our clothes less, or demanding stricter environmental laws, each of us can make a difference. The next time you pick up a shirt for $5, remember that the real cost might be a poisoned river or a fish full of plastic.

John is a professional blogger and passionate advocate for environmental sustainability. With years of experience exploring eco-friendly practices and green innovations, he shares insightful articles on Planet Flagship to inspire a sustainable future. John’s expertise lies in making complex environmental topics accessible and actionable, empowering readers to make meaningful changes for the planet.