What are National Parks?

A national park is a designated area protected by a country’s government to conserve the environment. A national park may be established for the benefit and amusement of the general public or due to its historical or scientific significance. In Future of National Parks, the majority of the landscapes and the flora and fauna that coexist with them are preserved in their natural state.

Why are they important?

National parks protect ecological biodiversity, maintain landscapes, act as anchors for broader ecosystems (such as wildlife corridors), and sustain natural and cultural resources economically through tourism and other means.

Additionally, national parks provide peaceful spaces for introspection, promote health and well-being, and support public education about the value of conservation.

Global ecosystems are changing due to climate change, and national parks, once thought to be secure havens for biodiversity, are becoming increasingly susceptible. The delicate balance of plants and animals in these protected regions is being upset by rising global temperatures, changed rainfall patterns, and an increase in the frequency of extreme weather events. Climate change is forcing ecosystems to adapt more quickly than they can on their own, as seen by the melting of glaciers in alpine parks and the bleaching of coral in marine reserves.

These effects extend beyond specific parks and stem from a broader global issue that jeopardizes the fundamental goal of conservation initiatives. National parks must maintain their ecological integrity amid a rapidly changing world due to global warming.

READ MORE: Mangroves: The Unsung Heroes of Climate Change Mitigation

How Climate Change is Affecting National Parks

- Rising Sea Levels

Rising sea levels have the potential to flood coastal communities and freshwater habitats, endangering historic buildings in dozens of national parks along America’s coastlines and damaging plant and animal life. The lush subtropical environment of Everglades National Park is unique in its richness and beauty. This well-liked park has been designated as a Ramsar Wetland of International Importance, an International Biosphere Reserve, and a World Heritage Site.

The equilibrium of fresh and salt water is essential to the Everglades. This variety of habitats supports numerous rare and endangered animal and plant species. This park is home to hundreds of species, including manatees, unique orchids, endangered Florida panthers, dolphins, crocodiles, alligators, and roseate spoonbills.

However, this unique area famously known as a “river of grass” is only one of many coastal regions that are seriously threatened by sea level rise. Because of their very level terrain, the Everglades are particularly susceptible to having their bays, estuaries, woodlands, marshes, prairies, and tidal flats swamped by saline water. The imbalance is worsened by the fact that the area is already severely short of fresh water, which no longer naturally flows in large quantities due to long-term development and industrial demands.

- Water Availability and Drought:

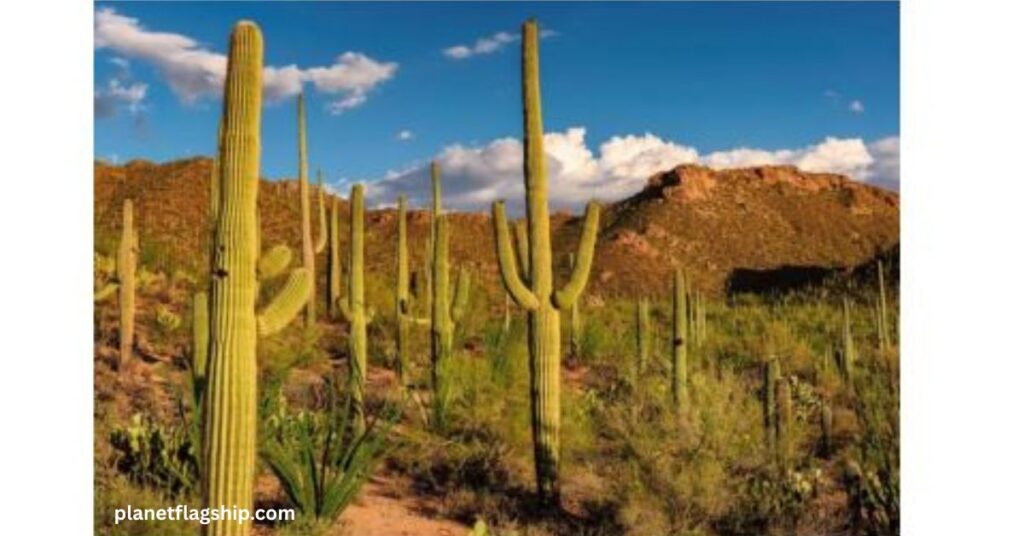

Only found in the Sonoran Desert, the saguaro cactus is a unique symbol of the American Southwest. The tallest cactus species in the nation, this towering plant can reach 60 feet and live for more than 200 years. Many desert dwellers love and identify with these majestic, long-lived, multi-armed plants, and the adjacent Tohono O’odham Nation uses their fruit as a culturally significant food source.

To protect these cherished cacti, President Herbert Hoover designated the area as a national monument in 1933. This site was formally designated as Saguaro National Park in 1994.

Rain is essential to the life of these massive saguaros. To maximize the plants’ capacity to absorb water during winter and summer rains, the majority of their intricate root systems extend as wide as the cactus is tall and develop only 4 to 6 inches below the surface.

Since the early 1990s, when temperatures started to rise sharply and the area experienced a protracted drought, fewer new saguaros have established themselves at Saguaro National Park. Younger saguaros are struggling to grow as the climate crisis makes desert winters drier and warmer.

Invasive buffelgrass, which outcompetes almost all of the park’s native vegetation and is significantly more combustible than other local species, like saguaros, has also proliferated due to warmer winters. Buffelgrass can destroy these slow-growing cacti and make it harder for them to survive in their namesake park by causing hotter, more intense fires.

- Loss of Snow and Ice:

In areas like Gates of the Arctic National Park, the rapid thawing of permafrost is changing the landscape as Alaska’s southern glaciers lose over 75 billion tons of ice each year. Within 30 years, glaciers at Montana’s Glacier National Park may vanish entirely, permanently, from the park that bears their name, having a profound impact on the ecosystem as a whole.

In addition to altering park grounds and waters, glacial melt and the loss of snow and ice endanger wildlife species such as wolves and foxes, which rely on these elements for survival. In warm-weather seasons, the loss of snowpack can potentially significantly exacerbate drought conditions.

Pedersen Glacier, at Aialik Bay in Alaska’s Kenai Mountains, in 1917 (left) and 2005 (right). In the early 20th century, the glacier met the water and calved icebergs into a marginal lake near the bay. By 2005, the glacier had retreated, leaving behind sediment that allowed the lake to be transformed into a small grassland.

- Fire:

Wildfires frequently threaten parks across the West, and as a result of climate change, the threats are getting worse. Of all U.S. parks, wildfires are anticipated to increase most significantly in Yellowstone, Glacier, and Rocky Mountain National Parks. In regions where fires were previously uncommon, such as the Southeast, warmer temperatures are also increasing the likelihood of fires.

In 2016, a wildfire in the Gatlinburg area killed 14 people, damaged or destroyed over 2,500 homes, and burned 11,000 acres of Great Smoky Mountains National Park, coming within 2,000 feet of a major visitor center and requiring 14,000 residents to evacuate.

The 2018 Ferguson Fire, in the Sierra National Forest, Stanislaus National Forest, and Yosemite National Park in California, which killed two firefighters and caused millions of dollars in damage, forced evacuations, and created financial hardships for local businesses last summer.

- Invasive Species:

Because they outcompete native species, disturb ecosystems, and change natural processes, invasive species are becoming a greater threat to national parks in a warming world. Warmer temperatures, altered rainfall patterns, and milder winters are among the new environmental conditions brought about by climate change that enable non-native species to flourish where they were previously unable to. The natural balance that national parks are intended to preserve may be seriously harmed by this.

- Cheatgrass (Bromus tectorum) – Western U.S. Parks: This invasive grass spreads rapidly and increases the frequency and intensity of wildfires. Found in parks like Zion and Yellowstone, it replaces native grasses, threatening habitats for local wildlife.

- Emerald Ash Borer Great Smoky Mountains National Park (USA): This beetle has killed millions of ash trees in North America. Warmer winters have allowed it to spread faster and further, disrupting forest structure and local biodiversity.

- Lionfish- Biscayne National Park: Native to the Indo-Pacific, this fish thrives in warming ocean waters. It has no natural predators in the Atlantic and preys on native reef fish, damaging marine ecosystems.

Pakistan-Specific Case Study

Khunjerab National Park (Gilgit-Baltistan):

One of the highest-altitude protected areas in the world is Khunjerab National Park, located in the Karakoram Mountains. Famous cold-climate animals, including the Marco Polo sheep, Himalayan ibex, and snow leopard, can be found in this park. However, the region’s glaciers are melting more quickly due to rising temperatures driven by climate change, causing habitat loss, disrupted water cycles, and downstream flooding.

Additionally, alpine vegetation is being forced upslope, endangering the fragile food chain that sustains biodiversity at high elevations. Millions of people downstream who rely on these glaciers for freshwater are at risk due to ongoing glacial melt, as are the park’s fauna. Khunjerab is a stark illustration of Pakistan’s mountainous national parks’ extreme susceptibility to climate change.

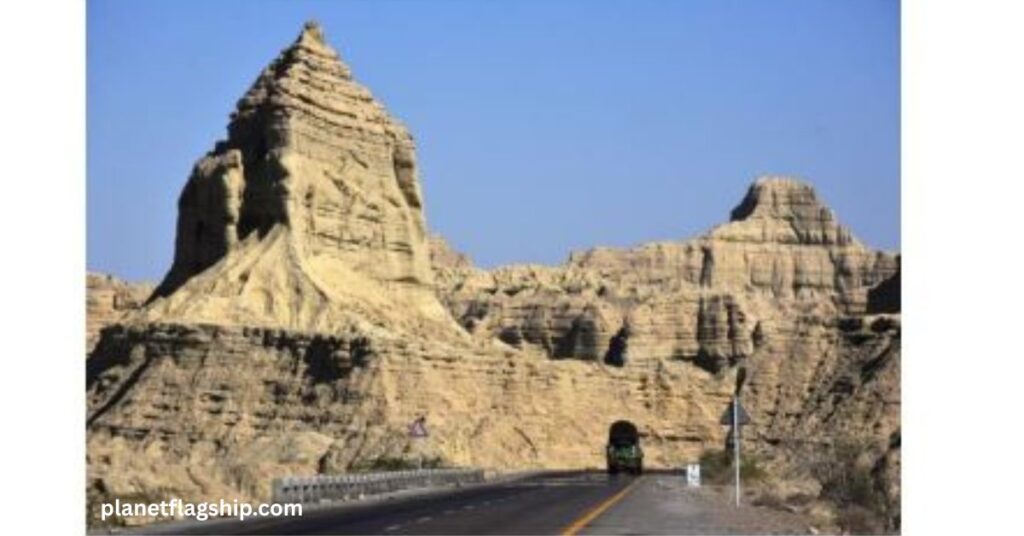

- Hingol National Park (Balochistan):

The largest park in Pakistan, Hingol National Park, features a remarkable blend of desert, riverine, and coastal habitats, but climate change is threatening its distinctive ecology. The delicate coastal areas and mangrove ecosystems are under threat from rising sea levels and changing monsoon patterns. Long-term droughts and rising aridity are straining freshwater supplies in inland areas, leading to habitat loss for species such as the marsh crocodile and the Sindh ibex.

Furthermore, wildlife and local human populations are compelled to compete more fiercely for dwindling resources as water becomes scarcer. Hingol is a prime example of how biodiversity and the fragile equilibrium between nature and human existence in dry coastal regions are both threatened by climate change.

- Kirthar National Park:

For animals like the Chinkara gazelle, striped hyena, and caracal, Kirthar National Park, which stretches across the untamed landscape between Sindh and Balochistan, is essential. Rising temperatures and prolonged droughts have dried up natural springs and degraded habitat quality in the park over the past few years.

Overgrazing and competition with natural herbivores result from the increased influx of livestock from nearby villages into the park in search of water and feed. Kirthar is under increasing ecological pressure from climate change, forcing both humans and animals into regions with limited resources. The park emphasizes the importance of comprehensive conservation policies that account for local livelihoods and environmental sustainability.

Human, Cultural, and Economic Impact:

- Indigenous communities and traditional knowledge:

Indigenous people in the vicinity of national parks possess important traditional knowledge about climatic cycles and local ecosystems. Climate change is disrupting wildlife, crop patterns, and grazing cycles in places like Gilgit-Baltistan and Chitral, endangering both traditional practices and livelihoods.

Notwithstanding these obstacles, their expertise such as seasonal awareness and appropriate land use—can aid in contemporary conservation. Climate resilience requires that these populations be included in park management.

- Tourism and revenue loss:

Due to landslides, unpredictable weather, and a decline in visual splendor, climate change is lowering visitation in national parks. Fewer people are visiting Pakistani parks like Deosai and Khunjerab, which reduces revenue for local businesses and park fees. Funding for conservation and the livelihoods of those who rely on ecotourism are both impacted by this trend. Long-term sustainability depends on encouraging safer, climate-resilient travel.

v Impact on park-based jobs and local economies:

Numerous people depend on occupations related to national parks, such as maintenance, guiding, and hospitality. These occupations are at risk as the effects of climate change intensify, including decreased tourism and ecological damage.

Communities that experience revenue losses in areas like the Kirthar and Margalla Hills may resort to unsustainable practices such as overgrazing or logging. Protecting people and the environment requires promoting green jobs and alternative forms of income.

Conservation and Adaptation Strategies:

- Ecosystem restoration and management: Replanting native species, restoring wetlands, and controlling invasive species help parks recover and adapt to climate stress.

- Climate-resilient species relocation: Moving vulnerable species to safer habitats can prevent extinctions as ecosystems shift due to warming.

- Involving local communities in sustainable conservation: Empowering locals with jobs, training, and shared decision-making strengthens conservation and supports livelihoods.

- Ecotourism and sustainable park funding: Promoting low-impact tourism and reinvesting revenues into park protection ensures long-term ecological and economic health.

FAQs: The Future of National Parks in a Warming World

How does climate change threaten national parks?

Climate change causes rising temperatures, altered rainfall, sea-level rise, glacier melt, wildfires, and invasive species. These changes disrupt ecosystems, destroy habitats, and threaten wildlife that national parks are meant to protect.

Why are glaciers and snow loss a serious issue for parks?

Melting glaciers and reduced snowpack affect water supply, increase droughts, and disrupt wildlife habitats. Parks like Glacier National Park may lose their glaciers entirely, permanently altering ecosystems.

How do invasive species increase due to climate change?

Warmer temperatures and milder winters allow invasive plants and animals to spread faster. These species outcompete native wildlife, increase fire risk, and damage natural balance in parks.

What challenges do Pakistan’s national parks face from climate change?

Parks like Khunjerab, Hingol, and Kirthar face glacier melt, drought, habitat loss, water scarcity, and increased human-wildlife competition, threatening biodiversity and local livelihoods.

What can be done to protect national parks in a warming world?

Solutions include ecosystem restoration, climate-resilient species management, controlling invasive species, involving local communities, and promoting sustainable ecotourism to fund conservation efforts.

ALSO READ: From Floods to Wildfires: The Rising Costs of Climate Disasters

Conclusion:

National parks face previously unheard-of difficulties in a warming climate, but we can protect their future by implementing focused conservation measures. Restoring ecosystems, moving species, and involving the local population are all essential to preserving resilience and biodiversity.

Furthermore, ecotourism can provide the funding needed for parks to be sustainable in the long run. We can make sure that national parks survive climate change and continue to benefit wildlife and future generations by combining research, traditional knowledge, and sustainable practices.

National park. (n.d.). Encyclopædia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/science/national-park

Natural Habitat Adventures. (n.d.). Why national parks matter. https://www.nathab.com/blog/why-national-parks-matter

National Parks Conservation Association. (n.d.). Rising sea levels. National Parks Conservation Association. https://www.npca.org/case-studies/rising-sea-levels

National Parks Conservation Association. (n.d.). Drought and water availability. National Parks Conservation Association. https://www.npca.org/case-studies/drought-and-water-availability

National Parks Conservation Association. (n.d.). Loss of snow and ice. https://www.npca.org/case-studies/loss-of-snow-and-ice

National Parks Conservation Association. (n.d.). Fire. https://www.npca.org/case-studies/fire

John is a professional blogger and passionate advocate for environmental sustainability. With years of experience exploring eco-friendly practices and green innovations, he shares insightful articles on Planet Flagship to inspire a sustainable future. John’s expertise lies in making complex environmental topics accessible and actionable, empowering readers to make meaningful changes for the planet.