Introduction

According to scientists and public health experts, climate change plays a crucial role in contributing to the next global pandemic. Humans have faced the vulnerability of the COVID-19 pandemic, which is an infectious disease caused by the coronavirus. Climate change is reshaping environments and transforming global health. As temperatures rise, ecosystems destabilize, weather patterns shift, and the risk of new infectious diseases increases dramatically as they spill over from animals to humans.

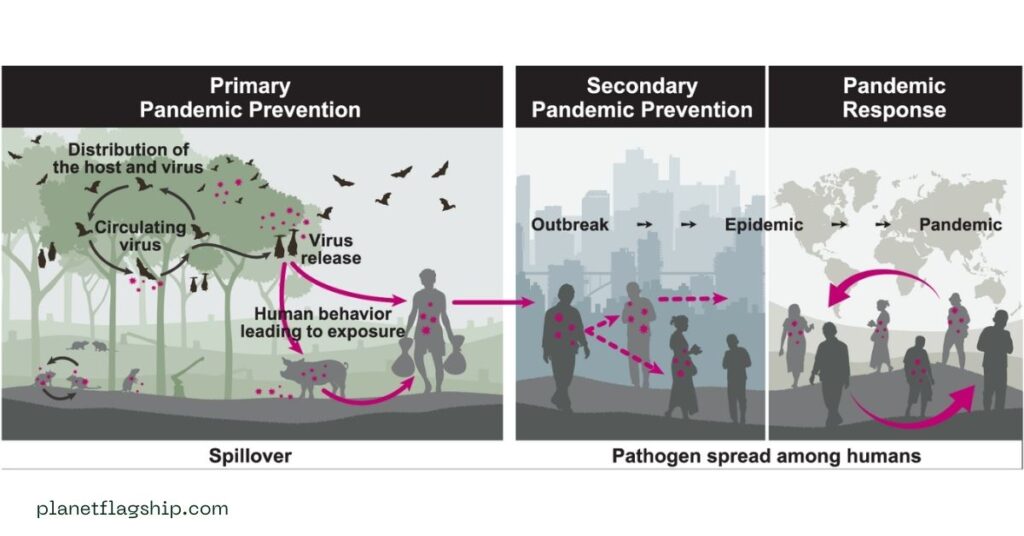

Climate change increases the risk of zoonotic spillover. This situation raises a question: Are we ready for the next climate-induced pandemic? Recent studies indicate that nearly 75% of emerging infectious diseases are zoonotic in origin, which is attributed to habitat loss and extreme weather events (Breithaupt, 2003). Although global awareness has improved, our healthcare system, environmental policies, and international coordination remain inadequately prepared.

The COVID-19 pandemic has led to significant improvements in health, particularly in terms of early detection, surveillance, and the rapid development of vaccines. However, the intersection of climate change and health preparedness remains under-addressed, leaving us dangerously unprepared to face the next climate-induced pandemic. This essay explains how climate change contributes to the emergence of new diseases and climate-induced pandemics, highlighting the preparedness gap and the steps needed to secure the future.

Climate change as a pandemic catalytic agent

Vector Expansion

Climate change is not only an environmental issue but also a public health threat. The effects of climate change alter the habitats of disease-causing vectors, including mosquitoes, ticks, and rodents. These changes affect the spread of diseases. Global warming causes the dispersal of mosquitoes and ticks to new regions. Optimal transmission temperatures of 25°C to 29°C for malaria and Zika are now occurring in previously cooler areas, causing vector-borne disease risks (Bullard, 2021).

Zoonotic Spillover and Habitat Loss

Human activities, including deforestation, agriculture, and urbanization, have destroyed wild habitats, forcing animals into closer contact with people and increasing the risk of zoonotic spillover. According to the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES), approximately 70% of emerging diseases are of zoonotic origin (Breithaupt, 2003).

Permafrost Risk and Dormant Pathogens

Melting of permafrost causes the release of ancient pathogens. A heatwave melted permafrost and uncovered the carcass of a reindeer that had died decades earlier from anthrax in Siberia in 2016. The revived bacteria infected dozens of people. Warming Arctic regions are melting permafrost, with documented cases of long-dormant anthrax resurfacing. This highlights the threat of ancient pathogens reemerging as global temperatures rise (Mackelprang et al., 2025).

READ MORE: Power of environmental Boycotting: Can conscious consumers change the world?

Current Global Vulnerabilities

Current global vulnerabilities include gaps in health infrastructure, limited data and surveillance, and political and financial inaction. No nation has been fully prepared for pandemics, according to the Global Health Security Index. Low- and middle-income countries are vulnerable, lacking workforce, critical surveillance, and vaccine access in the face of health threats because of climate change.

Despite advances in genomic sequencing and digital epidemiology, cross-sector data integration remains weak, and ~5% of climate funding is allocated to healthy adaptation (Ansah et al., 2024). Political will often lags behind scientific evidence. Initiatives like the Rockefeller Foundation’s call for integrated climate-health planning suggest numerous cities lack comprehensive systems to identify and address climate-driven disease risks. Estimates suggest that global investment falls short, requiring billions more to close preparedness gaps.

Health Frameworks

Integrated One Health systems and preparedness

The One Health approach is a collaborative model that links human, animal, and environmental health, which is vital for anticipating and containing the emergence of zoonotic diseases. This approach encourages collaboration across disciplines, including medicine, veterinary science, environmental science, and ecology, to detect and prevent zoonotic spillovers before they reach humans.

The World Bank, WHO, and other institutions have recognized this approach; however, implementation remains limited and underfunded (Wolmuth-Gordon & Mutebi, 2023). Numerous countries remain under-prepared. In low-income nations, health systems are vulnerable, lacking the resources, personnel, and infrastructure needed to respond to pandemics.

Climate and Virus Interactions Surveillance

Real-time monitoring of wildlife pathogens, climate trends, and vector distribution is important for detecting early outbreaks. AI-driven genomic analysis holds promise in predicting mutations and pinpointing viral hotspots. Both ecological and epidemiological data improve situational awareness.

The pandemic spurred advancements in vaccine technology, including mRNA platforms, and highlighted the importance of surveillance systems, such as genomic sequencing. The World Health Organization (WHO) and the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (CEPI) have prioritized pandemic prevention and response more seriously.

Dual-Purpose Investments

Synergies exist between pandemic preparedness and climate adaptation. McKinsey finds that $7–$25 billion in targeted investments could fortify both health security and climate resilience (Braithwaite, 2023). Areas such as health workforce training, resilient infrastructure, and integrated data systems serve dual functions.

COVID-19

The COVID-19 pandemic exposed the fragility of global healthcare systems, the dangers of misinformation, and the consequences of delayed action, but it also provided valuable lessons in vaccine development, international cooperation, and the role of public health infrastructure (Sheehan & Fox, 2020).

Challenges and Barriers

Fragmented Coordination

Effective One Health implementation remains limited by siloed governance, unreliable data sharing, and competing sectoral priorities. Low- and middle-income countries face capacity and resource constraints.

Funding Shortfalls

Most climate adaptation and pandemic preparedness funding remains distributed separately, with less than 5% targeting health resilience directly (Sheehan & Fox, 2020). Long-term investment is crucial for building scalable systems.

Public Trust and Misinformation

Misinformation during the COVID-19 pandemic emphasizes the fragility of public trust. Misinformation spread through social media and other platforms has eroded trust in public health institutions. Combating disinformation and promoting science-based communication is crucial for an effective pandemic response. Building transparent, science-based communication channels is important for climate-health readiness.

Political Inaction and Fragmentation

Numerous governments prioritize short-term economic gains over long-term health and environmental stability. Climate change and public health are often treated as separate issues, but they are deeply interconnected. Furthermore, nationalism and a lack of trust between nations can delay coordinated responses to global threats.

Inequity and Resource Distribution

Low-income and marginalized communities are often the most vulnerable to both climate change and pandemics. These groups face higher exposure to disease vectors, limited access to healthcare, and a reduced ability to recover from crises. A just and equitable approach is essential to ensuring that pandemic preparedness does not become a luxury reserved for the wealthy.

The Role of Climate Policy in Pandemic Prevention

Determining the root causes of pandemics related to climate change requires an approach to climate change that is not only an environmental issue but also a health imperative.

Mitigation and Adaptation Strategies

Greenhouse gas emissions, protecting forests, and conserving biodiversity are mitigation efforts to reduce the risk of future pandemics. Concurrently improving water and sanitation infrastructure, investing in climate-resilient healthcare systems, and developing early warning systems can help societies mitigate the health effects of climate change.

Technological and Scientific Readiness

Technology can play a vital role in pandemic prevention. Innovations in artificial intelligence, remote sensing, data analytics, and genomic surveillance can help detect disease outbreaks early and model their potential spread.

Surveillance and Early Detection

Robust surveillance systems are important for identifying emerging threats quickly. Platforms such as HealthMap and ProMED track outbreaks globally and can provide early warnings. However, many regions lack the infrastructure or political will to maintain and share exact health data.

Vaccine and Therapeutic Development

COVID-19 demonstrated the power of rapid vaccine development. Initiatives like the mRNA vaccine platform and global partnerships such as COVAX should be expanded to ensure equitable access to vaccines in the event of a future outbreak. Research into “prototype pathogens” should continue for the development of preemptive vaccines.

Case Studies

- Urban Dengue Models: Rio de Janeiro utilizes predictive models that combine weather data and surveillance to anticipate dengue outbreaks, enabling rapid public response.

- Permafrost Monitoring: Arctic viral surveillance offers crucial insights into emerging environmental threats, underscoring the importance of proactive ecosystem health monitoring.

- Livestock Vaccinations: Initiatives in Mongolia and Southeast Asia demonstrate that vaccinating animals against brucellosis significantly reduces human cases, highlighting the economic and health benefits of a One Health approach.

Recommendations

We must take a proactive, integrated, and globally coordinated approach to prepare for the next climate-induced pandemic. The following recommendations are essential:

- Build and strengthen health infrastructure, especially in vulnerable regions, to withstand climatic shocks.

- Strengthen global health governance and cooperation through organizations like the WHO, which ensure equitable access to healthcare resources.

- Inspire collaboration and invest in surveillance systems that monitor human, animal, and environmental health.

- Develop transparent, real-time data systems for quick detection of and response to outbreaks.

- Reduce emissions, protect ecosystems, and slow the pace of environmental degradation that increases disease risks.

- Support science communication, education, and public engagement to build trust and promote informed decision-making.

- Fund research into emerging pathogens, vaccine development, and climate-health linkages.

FAQ’s

How does climate change increase the risk of pandemics?

Climate change disrupts ecosystems, bringing humans into closer contact with animals and disease-carrying vectors like mosquitoes and ticks. Rising temperatures expand the range of infectious diseases such as malaria and Zika. Melting permafrost also threatens to release ancient, dormant pathogens back into circulation.

What is a climate-induced pandemic?

A climate-induced pandemic refers to an outbreak of infectious disease triggered or accelerated by environmental changes. Factors like deforestation, habitat loss, and extreme weather events increase zoonotic spillovers. These conditions create the perfect storm for diseases to jump from animals to humans and spread rapidly.

Why are we still unprepared for the next pandemic?

Despite advances in vaccines and surveillance after COVID-19, health systems remain fragmented and underfunded. Less than 5% of climate funding goes toward health resilience. Political inaction, misinformation, and global inequities leave vulnerable populations dangerously exposed to future outbreaks.

What role does the One Health approach play in prevention?

The One Health approach links human, animal, and environmental health to stop pandemics at the source. It fosters collaboration across medicine, veterinary science, and ecology to detect threats early. Implementing this model can significantly reduce zoonotic spillovers and strengthen resilience worldwide.

How can we prepare for climate-induced pandemics?

Preparation requires stronger surveillance, climate-resilient healthcare, and rapid vaccine development. Global cooperation and fair resource distribution are vital to ensure equity in responses. By investing in prevention today, we can stop the next pandemic before it begins.

Conclusion

The next pandemic may emerge from melting Arctic ice, which could be carried by a displaced bat or incubated in a flood-ravaged region where humans and animals are forced into unnatural proximity. Climate change is a pandemic accelerant that increases the likelihood and severity of infectious disease outbreaks. We have learned valuable lessons from the COVID-19 pandemic. Humanity finds itself at a pivotal juncture. The knowledge, tools, and foresight to prevent the next climate-induced pandemic are within reach, but readiness demands political will, urgent action, and global solidarity.

We are not yet fully prepared for the next pandemic. However, readiness is not a fixed state; it can be built. The time to take action is before climate change writes the next chapter in the history of pandemics. Climate change is reshaping disease landscapes and powering the emergence of zoonotic threats. The melting of permafrost, the range expansion of vectors, and increased wildlife-human interactions all increase the risk of pandemics. While the global community has made strides in surveillance and vaccine platforms since the COVID-19 pandemic, fundamental weaknesses persist. Fragmented health systems, insufficient integration of One Health, political apathy, and scarce investment leave us dangerously exposed.

However, the path forward is illuminated by adopting a fully resourced One Health framework, investing in climate-resilient health infrastructure, and leveraging data-driven artificial intelligence for surveillance, which can simultaneously mitigate climate and pandemic risks. Cities’ success in dengue forecasting, livestock vaccine programs, and Arctic pathogen monitoring shows the power of integrated responses. We stand at a critical juncture, and continuing down a path of siloed action will deepen vulnerabilities. However, embracing coordinated, interdisciplinary, and internationally funded strategies presents an opportunity to avert the next global catastrophe.

References

- Breithaupt, H. (2003). Fierce creatures: Zoonoses, diseases that jump from animals to humans, are a growing health problem around the world. Understanding their causes and their effects on humans has therefore become an important topic for global public health. EMBO reports, 4(10), 921-924.

- Mackelprang, R., Barbato, R. A., Ramey, A. M., Schütte, U. M., & Waldrop, M. P. (2025). Cooling perspectives on the risk of pathogenic viruses from thawing permafrost. mSystems, e00042-24.

- Bullard, R. D. (2021). 2021 Charles C. Shepard Science Awards: Climate change as a public health threat: why equity matters:Wednesday, October 20, 2021 • 1:00PM to 3:30PM.

- Ansah, E. W., Amoadu, M., Obeng, P., & Sarfo, J. O. (2024). Health systems’ response to climate change adaptation: a scoping review of global evidence. BMC public health, 24(1), 2015.

- Braithwaite, J., Dammery, G., Spanos, S., Smith, C. L., Ellis, L. A., Churruca, K., … & Zurynski, Y. (2023). Learning health systems 2.0: future-proofing healthcare against pandemics and climate change. A White Paper.

- Wolmuth-Gordon, H., & Mutebi, N. (2023). Public health and climate change: A One Health approach.

- Sheehan, M. C., & Fox, M. A. (2020). Early warnings: the lessons of COVID-19 for public health climate preparedness. International Journal of Health Services, 50(3), 264-270.

John is a professional blogger and passionate advocate for environmental sustainability. With years of experience exploring eco-friendly practices and green innovations, he shares insightful articles on Planet Flagship to inspire a sustainable future. John’s expertise lies in making complex environmental topics accessible and actionable, empowering readers to make meaningful changes for the planet.