Introduction

The world is grappling with numerous environmental issues, including rapid climate change and the overwhelming quantity of plastic debris in our oceans. These sorts of things can leave individuals feeling hopeless, questioning whether their daily decisions have any actual impact. But one place where consumer behavior is not insignificant in the marketplace. How we use our money can provide powerful signals to businesses, particularly when consumers collectively refuse to spend money on enterprises with negative environmental impacts. This action, also known as environmental boycotting, has proven to be a highly effective tool for the public.

The concept of environmental boycotting has been thoroughly examined in this paper. It traces its history, analyzes the psychology behind why individuals boycott, and measures the effectiveness of such actions in producing tangible change in the real world. Case studies of effective campaigns, along with analyses of their limitations and negative consequences, are revealed.

The boycott aims to assess the effectiveness and timing of the approach. Although not a panacea, consumer boycotts can and have influenced corporate practices in a more sustainable direction.

The Roots of Environmental Boycotting

Historical Context and Early Examples

Boycotting has been employed as a form of protest for centuries, but it gained prominence in the late 20th century.

The century when environmental boycotts became prominent. One of the first and most notable environmental boycotts was the tuna boycott of the 1980s. This boycott, led by environmental organizations like the Earth Island Institute, was directed against tuna businesses that used fishing practices that resulted in dolphin killing. The campaign played a key role. In developing the “dolphin-safe” label, which helps change the fishing industry toward more sustainable methods (Nolan, 2001).

Another notable instance is the Shell Boycott during the 1990s, started by the company’s

Plans for disposing of the Brent Spar oil platform in the North Sea were controversial. Environmental activists and consumers joined forces in a campaign against the move, forcing Shell to abandon the plan and seek a more environmentally friendly alternative (Greenpeace, 1995). These initial victories showed the effectiveness of boycotts in influencing corporate actions and raising environmental awareness.

ALSO READ: WHY WOMEN AND CHILDREN SUFFER THE MOST FROM CLIMATE DISASTERS?

The Rise of Consumer Activism

As concerns over the environment increased in the 1990s and early 2000s, boycotts were becoming a common strategy for activist consumers. Perhaps the most iconic movement was the global campaign to limit the use of single-use plastics. Plastic pollution is now one of the most significant environmental crises facing our generation, with millions of tons of plastic entering the oceans each year. In response to this crisis, consumers began boycotting plastic items, particularly plastic bags and straws, and the boycott has led to bans in over 120 countries (European Commission, 2019).

Similarly, palm oil boycotts have emerged as a central initiative of environmental consumerism. Palm oil is used in more than half of all packaged products, but its production is associated with rampant deforestation, habitat loss, and human rights violations. The pressure for sustainable palm oil has led to the development of certification schemes, such as the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO), which have compelled companies to adopt more sustainable sourcing practices (WWF, 2020).

The Psychology of Green Consumerism

Why Do People Boycott?

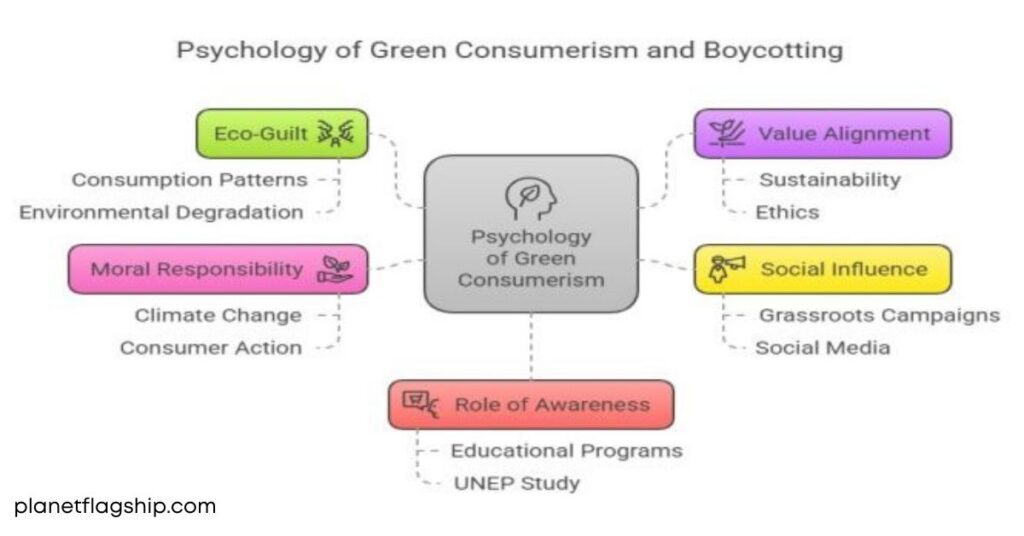

A mix of values, sentiments, and social factors precipitates environmental boycotting. There are a few psychological factors that explain why people opt to participate in boycotts:

Eco-Guilt: The perception that our consumption patterns lead to environmental degradation may evoke feelings of guilt. The guilt of many people may prompt them to change their behavior and refrain from patronizing companies that harm the environment (Kollmuss & Agyeman, 2002).

Value Alignment: Boycotting enables consumers to align their purchasing decisions with their environmental values. By choosing not to use products from companies that are not environmentally conscious, consumers can demonstrate their commitment to sustainability and ethical practices.

Social Influence: Grassroots campaigns and social media are widely utilized to raise awareness and promote boycotts. When an individual boycotts, it motivates others to do the same, resulting in a ripple effect that amplifies the boycott’s impact (Diani, 2000).

Moral Responsibility: With worsening environmental crises, such as climate change, most consumers feel that they have a moral responsibility to act. Boycotting the offending products is a means to act, however small, in response to global problems (Cohen & Green, 2011).

The Role of Awareness

Consumer boycotts typically gain traction through awareness campaigns. The better consumers understand the environmental footprint of their buying, the higher the chances they will make eco-friendly purchases.

A study by the United Nations Environment Program (UNEP) shows that informed consumers are more likely to practice environmentally friendly habits (UNEP, 2018). Educational programs, films, and social media campaigns have all been

instrumental in creating awareness regarding the environmental effects of consumerism.

Environmental Boycotts in Practice

The Plastic Backlash: A Success Story

Perhaps the best example of a successful environmental boycott is the international campaign to eliminate single-use plastics. Plastic pollution is one of the most significant ocean pollutants, and consumer boycotts have prompted major companies to change their operations. A 2019 European Commission report estimated that over 8 million tons of plastic waste flowed into the oceans annually, posing a significant threat to marine life and ecosystems.

In response to increased public pressure for change, several companies have committed to removing plastic straws, bags, and packaging. Starbucks and McDonald’s, for instance, have pledged to eliminate plastic straws from their operations and replace them with biodegradable or recyclable alternatives. IKEA has also promised to phase out single-use plastics from its offerings by 2020 (IKEA, 2020). Such efforts show the impact of consumer boycotts on corporate behavior and the promotion of sustainable alternatives.

Palm Oil Boycotts: Pushing for Sustainability

Another great success story is the palm oil boycott. Palm oil is used in numerous consumer goods, but its production has been linked to significant deforestation, which endangers biodiversity and contributes to climate change. As consumer consciousness of these problems increased, boycotts of unsustainable palm oil-containing products became widespread.

Firms such as Nestlé, Unilever, and Coca-Cola have responded to consumer pressure by committing to using only sustainably sourced palm oil. The creation of the RSPO, a certification system for sustainable palm oil, has contributed to such changes. There are still challenges, including issues such as illegal deforestation and land grabbing, but consumer boycotts have contributed to encouraging improved practices in the palm oil sector (WWF, 2020).

Challenges to Environmental Boycotting

The Cost Barrier

One of the biggest drawbacks of environmental boycotting is that sustainable alternatives cost more. Organic produce, green goods, and fair-trade items cost more than their non-organic, non-green, and non-fair-trade counterparts, respectively, and therefore are out of reach for lower-income consumers.

This acts as a hindrance to the broad implementation of sustainability.

Practices and underscores the necessity of cheaper, eco-friendly alternatives (Ostrom et al., 2019).

Greenwashing: Misleading Consumers

Another challenge is greenwashing, where corporations misrepresent themselves as environmentally friendly to appeal to environmentally conscious customers.

Such Misrepresentation discourages boycotts and makes it more difficult for consumers to differentiate between companies that truly are sustainable and companies that pretend to be (Delmas &

Burbano, 2011).

The Ripple Effect of Conscious Consumerism

Although conscious consumers by themselves cannot change the world overnight, their decisions have the power to create significant ripple effects. By choosing ethical brands, minimizing waste, and challenging unsustainable norms, they send a message to companies and governments that the environment matters.

These choices build cultural momentum, drive innovation, and establish new market standards. While systemic reform is necessary for broad change, consumer behavior plays a crucial role in determining the success of that reform. Essentially, conscious consumers may not save the world on their own, but they are usually the ones who initiate the change that others follow.

FAQ’s

What is environmental boycotting?

Environmental boycotting is when consumers collectively refuse to buy products or services from companies that harm the environment. This form of activism pressures businesses to adopt more sustainable practices.

Historical examples include the tuna boycott of the 1980s, which led to “dolphin-safe” labels, and the 1990s Shell boycott that forced the company to change its oil platform disposal plans.

How do consumer boycotts impact corporate behavior?

Consumer boycotts influence companies by creating financial and reputational pressure. When enough people stop buying harmful products, brands are forced to change practices to avoid revenue loss and public backlash.

Campaigns against single-use plastics and unsustainable palm oil have pushed major corporations like Starbucks, McDonald’s, and Nestlé to adopt greener policies.

Why do people participate in environmental boycotts?

People boycott for reasons like eco-guilt, value alignment, social influence, and moral responsibility. Eco-guilt comes from knowing consumption patterns damage the planet, while value alignment allows purchases to match personal ethics. Social influence and awareness campaigns, especially on social media, further motivate participation.

What are the main challenges of environmental boycotts?

Two major challenges are cost barriers and greenwashing. Sustainable alternatives often cost more, making them inaccessible for lower-income consumers. Greenwashing when companies falsely claim eco-friendliness misleads consumers and undermines boycott effectiveness, making it harder to identify genuinely sustainable brands.

Can boycotting alone solve environmental problems?

No, boycotting alone is not enough. While it can drive significant change, long-term environmental solutions require systemic reforms, strict government regulations, corporate accountability, and technological innovation. Boycotts are most powerful when combined with policy advocacy and sustainable production practices.

Conclusion

Environmental boycotting is an effective and growing mechanism that enables consumers to exert meaningful leverage on firms and industries that contribute to environmental damage. Though no panacea, consumer-initiated boycotts have already proven themselves capable of generating fundamental changes in corporate conduct and public policy. Plastic waste, unsustainable palm oil, and fast fashion campaigns have driven changes in product lines.

Enhanced supply chain transparency and convinced some major corporations to adopt more sustainable practices. These efforts demonstrate the combined force of mindful consumerism.

Alongside exerting financial pressure on firms, environmental boycotts serve a crucial function in raising public consciousness. They focus attention on vital issues and bring them into the mainstream, prompting people to reconsider their consumption patterns and opt for greener, more ethical options. This shift in consumer behavior conveys a powerful message: that environmental accountability is not an option, but a necessity.

Yet, boycotting can help resolve some of the complex issues surrounding the environmental crisis. It must be part of a larger set of policies that comprise tough government regulations, corporate accountability, technological change, and systemic reform toward sustainable consumption and production. Without these base supports, the effectiveness of consumer action will always be limited.

Ultimately, each time we make a purchase, we are casting a vote for the world we wish to inhabit. By being aware, advocating for stronger environmental policies, and choosing to support businesses committed to sustainability, we can help create positive change. Environmental Boycotting, with systemic reform, can help lead the way toward a more equitable and sustainable future.

References

Cohen, M. A., & Green, M. L. (2011). The moral imperative of sustainability. *Journal of Environmental Ethics*, 23(4), 331-348.

Diani, M. (2000). Social movements and collective action: Theories and strategies. *Oxford University Press*.

Delmas, M. A., & Burbano, V. C. (2011). The drivers of greenwashing. *California Management Review*, 54(1), 64-87.

European Commission. (2019). Single-use plastics: Bans and other measures. *EU Report*.

Greenpeace. (1995). Shell, Brent Spar, and the environment. Greenpeace International.

IKEA. (2020). Sustainability and IKEA’s commitment to eliminating single-use plastics.

IKEA Report*.

Kollmuss, A., & Agyeman, J. (2002). Mind the gap: Why do people act environmentally, and what are the barriers to pro-environmental behavior? *Environmental Education Research*, 8(3), 239-260.

Nolan, M. (2001). The tuna boycott: A case study in consumer activism. *Environmental Politics, 10(2), 57-75.

Ostrom, E., et al. (2019). The challenge of sustainable consumption. *Journal of Environmental Economics and Management*, 90, 123-143.

UNEP. (2018). The role of consumer behavior in promoting sustainability. *United Nations Environment Programme*.

WWF. (2020). Sustainable Palm Oil: A Guide for Companies. *World Wildlife Fund*.

John is a professional blogger and passionate advocate for environmental sustainability. With years of experience exploring eco-friendly practices and green innovations, he shares insightful articles on Planet Flagship to inspire a sustainable future. John’s expertise lies in making complex environmental topics accessible and actionable, empowering readers to make meaningful changes for the planet.